More comparisons between the British countryside of today and that from 1959-1961 in the paintings of Charles Tunnicliffe in the Ladybird "What to look for..." series of books.

“With blotched brown uppers and undersides light gray

They feed on sea weed beaches all the day

Some times in pairs or small flocks though seldom one alone

These little wandering birds called Turnstone.”

Francis Duggan, from “On seeing a pair of turnstone”

(Copyright: Ladybird Books)

Summer Picture 22

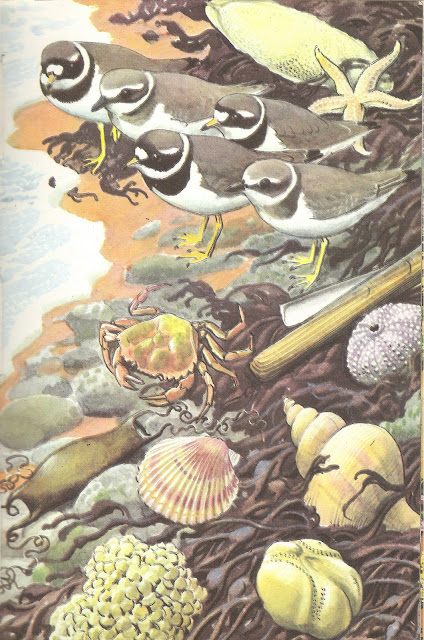

The last three pictures in the Ladybird Summer book, this one and the following two are hardly typical Summer scenes, although this picture and the final one are definitely meant to represent some transition to Autumn (as you’ll see again in a couple of posts’ time). This picture is a relatively simple scene, with a flock of little brown, black and white wading birds, called turnstones, foraging through some brown seaweeds, or wracks (knotted or egg wrack, bladder wrack and saw wrack). In the background, another flock of turnstones is flying away, looking like mini-oystercatchers. Some common mussels (sometimes called blue mussels) are visible under the wracks.

The turnstone (Arenaria interpres) is a common bird on British shores in Winter, as well as a passage migrant recorded in Spring and Autumn. As my old "AA Book of Birds" says of this species: “The greatest numbers gather on rocky and stony beaches, where the seaweed covers a rich supply of food.” The name “turnstone” comes from their habit of flipping over stones, sticks, shells and seaweed to uncover their prey of sandhoppers (the little jumping shrimps you commonly see when you move seaweed or driftwood on the tideline), little shellfish, insects, young fish and carrion, and they have also been recorded as eating bird’s eggs. They can turn over stones nearly equal in weight to their own body. The foremost individual in the picture is still in summer plumage, while the others have clearly moulted to reveal their more drab winter colours. In summer, nearly all the turnstones that have over-wintered in Britain return north to the Arctic to breed, so these birds in the picture are either on passage or have arrived here to over-winter.

My usual source of trend information of birds for this blog, the British Trust for Ornithology, unfortunately doesn’t have an entry for this species. But my bird book, “The Birds of the Western Palearctic” reports that the British wintering population is a minimum estimated 44,500 birds. It also suggests that there is no real idea of the total European population as many birds inhabit remote unsurveyed rocky shores of Iceland, Ireland and Norway. Since no sources that I regularly access for this series of posts provides any indication of a decline, I thought I’d be unable to comment on the status of the turnstone. At the last minute, however, coming unbidden through the postal system, like the US 7th Cavalry coming over the hill in the nick of time (but without the unfortunate anti-Native American connotations of that historical analogy, obviously!), a report arrived – the 2010 State of the UK’s Birds report. Produced by a long list of conservation agencies and bodies (including the Royal Society for the Protection of Birds and the British Trust for Ornithology), this indicates that between 1981 and 2007, the turnstone overwintering population in the UK has increased by some 17%, although in the last ten years there has been a 6% decline.

I’m not going to say much about any of the brown wracks or the common mussels – they are all very common species, likely all still to be doing very well, thank you very much, and all deserve more attention than I can give them here. If you want to look for yourself, I recommend once again that you look at the MARLIN website (Marine Life Information), where you can find information on the distribution and biology of these species.