More comparisons between the British countryside of today and that from 1959-1961 in the paintings of Charles Tunnicliffe in the Ladybird "What to look for..." series of books.

"See how steadfastly they stand

the cormorants of Lympstone Sand

in ranks, like booties on parade,

with all their better parts displayed.

They face up nobly to the wind

and neatly tuck their tails behind

and number off from left to right.

Their hearts are true. Their eyes are bright.

They never twitch or jig about

But hold their heads high, chest puffed out

and perk their bills up, if you please,

to smackbang forty five degrees.

These cormorant of Lympstone Sand

defer to none in all the land

nor ever let their bearing flag

lest some fond souls might think them shag."

Ralph Rochester, "Cormorant"

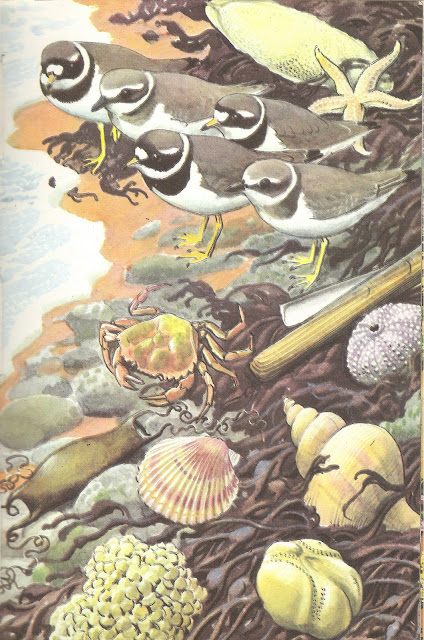

(Copyright: Ladybird Books)

Summer Picture 24

Oh, why has Summer felt like such a long season (in blogland, at least)? Here we are in November and I have FINALLY reached the final picture in the Ladybird Summer book! I find it interesting that the final three pictures have been around the seashore. I think that old Charles Tunnicliffe was well aware that, in terms of the approach of Autumn in Britain, as well as the harvest, the shortening days and the fall of dead leaves, the arrival of the birds that will spend the winter here is another key indicator – and they must, of necessity arrive first at the coast! While many species, like the redwings and fieldfares, will move on inland, the wading birds and many of the waterfowl will stay largely on the coast where, even in very cold winters, they will generally be able to feed on our many large estuaries. Hence, the selection of this image as the closing chapter of Summer in this (somewhat extended!) coverage of the Ladybird Summer book.

This picture is exclusively about birds – waders and waterfowl, gathered around the half buried ribs of a large wooden ship. A cormorant stands on one of the ribs drying its wings, lifting them into a breeze. Left of the centre of the picture, a solitary grey plover stands near some bar-tailed godwits, under the wooden ribs. Below them, a larger flock of knots stands, with a large flock of knot banking and turning against the slate grey sky in the background. In the foreground, a small flock of young sanderlings has landed down by the waterline.

I’ve always been really rubbish at identifying wading birds, especially the ones that arrive here in the winter, so it is lucky that the book provides text to tell me what is what here. In fact, the cormorant (which is not a wader anyway) is the only species here that I’d be confident in identifying without recourse to a bird book! So let’s start there…

A common, native, year-round resident fish-eating waterbird, the cormorant (Latin name: Phalacrocorax carbo) is a species that can raise high passions amongst the angling fraternity, where it is perceived to be a major consumer of the fish species also sought by trout fishermen. My old AA Book of Birds describes the cormorant, rather colourfully, as follows:

“Voracious, large-beaked, reptilian in appearance, the cormorant can consume more than its own weight of fish in a day.”

It’s a great line but it isn’t true (although the belief is probably still widespread among anglers. Managing conflicts between predators of commercially important prey species and the human exploiters of those prey is one of the key challenges for conservation in the UK (hen harriers/ red grouse, or peregrines/ racing pigeons also spring to mind) and the importance of good, sound, scientific evidence in developing policies to tackle these conflicts can’t be underestimated. And there has been quite a lot of research into the importance of cormorants as predators of stillwater fisheries in Britain, for example, from Loch Leven in east central Scotland. What is clear that male cormorants weigh 2-3 kg, while females are in the range 1.7-2.5 kg, and they usually require 4-500g of fish a day, well less than their own body weight. If you want a good explanation of the issues and how fishery managers are recommended to deal with their cormorant “problem”, there was a very useful fact sheet produced in England by the Fisheries and Angling Conservation Trust, along with a wide range of environmental, angling and conservation organisations. The most up-to-date information on trends in cormorant numbers is provided by the British Trust for Ornithology which suggests that the trend is for an increasing population, with over 9000 breeding pairs in the period 1998-2002. The BTO also says: “There was a 10% increase in the UK population between full surveys in 1985–88 and 1998–2002 … Trends during 1986–2005 show decreases in Scotland and in northeast and southwest England, but no trend in Wales, and steep increases inland in England and in regions bordering the northern part of the Irish Sea... Reasons for recent decline probably include increased mortality from licensed and unlicensed shooting.” The overall increase in population size was 37% between 1995 and 2008:

(From: British Trust for Ornithology)

Coming back to the bird in this picture, unlike many waterbirds, the cormorant’s plumage is, somewhat inconveniently for a diving, fish-eating waterbird, not waterproof, hence the reason that they often stand on rocks or, as here, other waterside structures, wings out-stretched to dry off in the wind after fishing.

The solitary Grey Plover (Pluvialis squatarola), on the centre-left of the picture is, for all its drab winter plumage shown here, a representative of a rather interesting species. I can’t do better than quote, again, from the AA Book of Birds: “The grey plover, drab in its grey-brown winter plumage and sometimes looking the picture of dejection as it waits on the mud-banks for the tide to turn, is a vastly different bird on its breeding grounds in northern Russia and Siberia. There, in its handsome summer plumage – grey-spangled, white-edged and black-breasted – it plunges and tumbles acrobatically in the air and will boldly attack marauding skuas that come too near its nest.” So, there’s more to this little tundra-loving, Cossack of a wading bird than meets the eye…

The BTO reports that around 53000 grey plover spend their winter in Britain, with perhaps 70000 passing through on migration and that, globally and in Europe, the species is not of conservation concern (although it has an “amber” warning status here in the UK – although it doesn’t say exactly why! Just something about Britain having an important non-breeding population). In winter, it feeds on our estuaries and coasts, mostly on marine worms, crustaceans and molluscs. From the above, I would say it seems unlikely that it has declined since the publication of these Ladybird books, but it is hard to be sure from the published evidence I can find. I did find, in the “Birds of the Western Palearctic”, however, that there has been a major recent increase (recent in their terms, being in the 1990s!) in the grey plover population of north-west Europe, this presumably including Britain.

Standing under the cormorant is a flock of five bar-tailed godwits (Limosa lapponica), which will have arrived on this British shore from Scandinavia or northern Russia, again to spend the winter here (or perhaps in transit to a destination much further south, using the British estuaries as staging posts, to rest and refuel on their migration flight. Like the grey plover, another wading bird that appears drab in winter plumage, the male bar-tailed godwit has a magnificent pale chest in the summer breeding season. The “Birds of the Westrn Palearctic” reports maybe 60,800 individuals in Britain in winter, while the BTO reports 62,000 winter birds. This species is not of conservation concern at European or Global level and its population may have increased within its breeding range. Interestingly, the BTO reports that, quite remarkably, Bar-tailed godwits from Alaska over-winter in New Zealand, but make the 11,000 km journey without stopping, which takes around seven days, probably the longest non-stop journey of any bird.

The largest flock on the shore is the small pale grey wading bird known as the knot (Calidris canutus). Yet again, this tiny wader makes enormous migratory journeys, from their breeding grounds in the far north of the Arctic in huges flocks to over-winter further south, arriving on Britain’s coasts in late summer and on into October. Many are only here on passage to further south, but huge flocks do remain for the winter. In fact, the BTO provides a figure, for the British wintering knot population, of 284,000!

What Charles Tunnicliffe has done in this picture is to include the knot, both as a flock in the foreground, but also as a massive wheeling flock in flight in the background, against the slate-grey sky. I grew up watching such unbelievably massive flocks of knot as a common winter sight on Aberlady Bay, east of Edinburgh, where I spent many cold winter and hot summer childhood days plodding across the nature reserve, my “Boots the Chemist” 8x30 binoculars in hand. Knot form these massive flocks, presumably for the same reasons as starlings are thought to do so – to reduce their individual chances of being taken by a raptor, most likely a peregrine falcon, and maybe because, by spending time roosting together, they are able to reduce heat loss and hence conserve energy during cold weather. And just like starling flocks, knots in flight wheel and bank apparently nearly simultaneously, with the effect that they flash light as you see all of their undersides turn towards you at once, the almost disappearing as they wheel back in the opposite direction, their darker backs against dark winter clouds. And the flock produces a hissing of wings if you are lucky enough to be near one in flight. One of Britain’s great estuarine spectacles, in my view, and one that is worth seeking out if you have the chance.

And so, and so, to conclude this series of blogs on the Ladybird Summer book, one final candidate species, in the nearest foreground of the picture, a small flock of ten young sanderlings. Yet another wader that breeds in the Arctic and comes to British coasts in the winter, where it prefers sandy shores, the sanderling (Canutus alba) can be described as a small pale wader that scurries along the tide line, restlessly looking for food, in the form of the small crustaceans of sandy beaches. In reading around for this article, I discovered a little bit of biological trivia that ties in with this distinctive movement of the sanderling: according to the BTO, “Uniquely amongst British waders, the Sanderling has no hind toe - giving it a distinctive running action, rather like a clockwork toy, as it darts away from incoming waves on the beach edge”! Perhaps 21,000 birds spend the winter here and the BTO describes little conservation concern over the status of this species in Britain, Europe or globally. Nice to end the Summer book and its blog posts on a small positive note!

Thanks for reading along so far, and for all the interesting comments. Hopefully, you’ll stay with me as I head into the Autumn book 9and try to catch up with the seasons bit – I DID start the Spring book late and have been playing catch up the whole time! On, on to Autumn (p.s. It is snowing heavily outside tonight! Did anyone see where Autumn went?)...