|

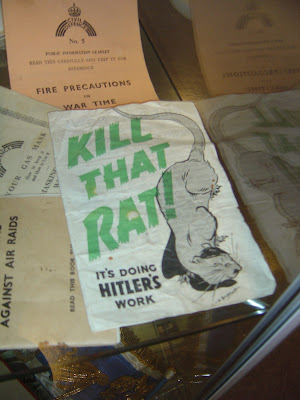

| Look at the moustache and haircut on the rat... |

Saturday, 30 October 2010

Friday, 29 October 2010

Big Wedge - prophetic or what?

Those old hippies, they know a thing or two...

Having just renewed my acquaintance with Fish's first solo album, "Vigil in a wilderness of mirrors" (updating my collection from a vinyl copy to CD and making it more convenient to listen to), I'd forgotten how powerful it was. I remember worrying in my relatively youthful fandom about whether this first solo effort would match up musically to what he had been doing previously in Marillion. I needn't have worried. It is a tour de force as far as first solo albums go - from the off, full of powerful and driving, or heartfelt and tender compositions. I think the song below was Fish's most successful solo single so far and, for me, one of the best on the album (and afforded us a chance to see him on Top of The Pops, if I recall correctly?). In light of the global credit crunch and the "living high on the hog", fairyland-of-credit lifestyles that people have been encouraged to lead and that contributed to that financial collapse (which may yet see me out of a job!), this song does indeed look highly prophetic and still sounds as cutting and incisive as it did at first hearing. I realise this is the second blog post in a row about Fish but it WAS a great show last Friday and I'm still a bit buzzing from it, so bear with me. Nature blog normality will be resumed shortly! For now though, enjoy the music!

Having just renewed my acquaintance with Fish's first solo album, "Vigil in a wilderness of mirrors" (updating my collection from a vinyl copy to CD and making it more convenient to listen to), I'd forgotten how powerful it was. I remember worrying in my relatively youthful fandom about whether this first solo effort would match up musically to what he had been doing previously in Marillion. I needn't have worried. It is a tour de force as far as first solo albums go - from the off, full of powerful and driving, or heartfelt and tender compositions. I think the song below was Fish's most successful solo single so far and, for me, one of the best on the album (and afforded us a chance to see him on Top of The Pops, if I recall correctly?). In light of the global credit crunch and the "living high on the hog", fairyland-of-credit lifestyles that people have been encouraged to lead and that contributed to that financial collapse (which may yet see me out of a job!), this song does indeed look highly prophetic and still sounds as cutting and incisive as it did at first hearing. I realise this is the second blog post in a row about Fish but it WAS a great show last Friday and I'm still a bit buzzing from it, so bear with me. Nature blog normality will be resumed shortly! For now though, enjoy the music!

Wednesday, 27 October 2010

Gone Fishin' ... (for marzipan)

So there I was, setting out to write a gig review and it's gone down a slightly odd path, as you'll see. On Friday last week, I was privileged to be able to see Fish, one of my oldest (as in longest-running, rather than in the geriatric sense) musical heroes playing to his home audience in Haddington, East Lothian. I've posted before about my youthful fandom for Marillion, and my enjoyment (modest understatement) of their music in their early days. Marillion's "Factor X" for me in those days was their frontman(mountain) Fish, Derek William Dick, all 10 foot tall of him (a bit like Mel Gibson's portrayal of William Wallace in the film "Braveheart" - "blowing fireballs and lightning from his ..." - media coverage of Fish's height has extended to the somewhat hyperbolic at times).

To my teenage progressive rock school friends and I, Fish was something of a rock legend - local (a Lothian boy from up the road in Dalkeith), even more deeply uncool than us (he wore kaftans, ferchrissakes!), and he played with this new band that everyone else thought was completely uncool (although surely the Tolkien reference in Marillion should have been worth a bit of street cred for teenage self-discovery - imagine if they emerged now, post Peter Jackson's Lord of The Rings!), playing prog rock music that we, the true cognoscenti, recognised for its instrumental virtuosity, its clever lyrics with their knowing puns, multiple entendres, strong personal, social and environmental messages and propensity to last more than four minutes per track.

At the time, for a generation of young prog rock fans who'd missed out on first-hand live experiences of Peter Gabriel's Genesis, the pre-nutjob ("The Wall") era Pink Floyd, and the classic Yes line-ups of the early and mid-1970s, Marillion were our new hope for complicated prog rock music, great live performances and high quality non-mainstream rock. And Fish, all 12 feet of him, was right up there, front of stage, all enigmatic , greasepaint-mask glowers, theatrical performance and exuberant exhorations to sing along ("You take the High road..."). We even had our own gig culture. Jethro Tull fans may have been given a big balloon to bat about the hall, but we threw buns to Marillion on stage (shouting: "Geezabun! As in "how does an elephant ask for a bun?" No, I don't really know how or why it started but I think it started at Edinburgh Marillion gigs, although I'm happy to be contradicted by evidence). We didn't know why we did it but it was our silliness and we loved it. Not sure if the enjoyment lasted as long for the band though!

Anyway, eventually, as music industry history and media coverage has recorded, Fish left Marillion and went "solo in the game" and has for some 20 years, ploughed his own furrow with a merry band of great musicians, turning out a series of great albums, as well as successful forays into acting, as an award-winning rock DJ on Planet Rock and, if you believe the Scottish Sun, a recent reinvention as an Action Man (welcome to my world, Big Man!)... allegedly giving up on women into the bargain ("I get my thrills from keeping fit now - I've had it with women" - Fish, there's something gone wrong here - I spent my young life keeping fit BECAUSE I couldn't find a woman!). Anyway, it was good to see him looking so fit and well last week!

So, after buying his first three solo albums and loving them, I kind of lost touch with what he was doing for a few years, but picked up again on his solo career a couple of years ago, when the epic 13th Star was released (Thanks for the heads-up at the time Pete M!). I was excited to discover recently that he was embarking on an acoustic tour, with just the three F's - Fish, Frank Usher, long-term guitar collaborator and Foss Patterson, long-term keyboard chum. I was even more excited to find that Haddington in East Lothian, Fish's base these days, was on the tour itinerary. I last saw Fish playing live, donkey's (15? 20?) years ago (what have I been doing?), with his full band (including Frank Usher and Robin Boult on guitars) in the Corn Exchange in Haddington. Last week, he was playing along the road in St Mary's Church, the largest church in East Lothian, even bigger than St Giles Cathedral in Edinburgh. Two gigs, Friday and Saturday nights, with the word on his Facebook site for fans being that both shows would be filmed and recorded for subsequent release, and that the production god Calum Malcolm (who produced Scotland's other finest atmospheric big space music guys, The Blue Nile) is lined up to weave his magic on the recordings - fantastic!

I could only make the Friday night and, even with a side visit to see my folks who live only a few miles away, I still managed to be in the first few to arrive before the show (just like the old days - we had so much spare time as teenage rock fans that Pete, Simon and I used to arrive at gigs HOURS before the show and just hang around - it worked out occasionally, we met Rory Gallagher once, which was great). I was beaten to the venue by four great Dutch folk and their German pal. Their presence confirmed what I've long suspected. The Dutch are (maybe) crazy. They came over for the long weekend FROM HOLLAND, just to see two Fish gigs in East Lothian. Crazy, but lovely and knowledgeable and absolutely devoted to Fish's solo music and his earlier Marillion material. You have to love proper fans, don't you?! Well done guys, I hope you had a grand weekend! Anyway, we were all there early enough to secure front row seats - brilliant! It was a very simple stage, pared down lighting rig and sound system, single chair for Frank and a Roland piano with stool for Foss (along with 15 foot high mike stand for the Big F). The backdrop of the church was, by contrast, quite magnificent, with high vaulted ceilings, tall stained glass arched windows and LOTS of wood and stone:

|

| St Mary's Church, Haddington - Fishbowl for the evening! |

I don't think the Friday gig was sold out and despite the size of the space above our heads (see above!), it felt quite intimate, perhaps on account of it actually being quite a narrow space (although long!). Fish opened the show with an unaccompanied version of Chocolate Frogs ("for a heid full of chocolate frogs what can you give to me?"). Now, I can't and won't give a track-by-track listing of the whole show - look elsewhere for that - I tend to live and enjoy live gigs in the moment and quite often can't remember afterwards exactly what I've heard song by song. In fact, I never intended to do so anyway, as the tour continues and I don't see why I should spoil all the surprises for folk still to see the show. But - impressions of the gig - Fish was clearly delighted to be back live in front of a home crowd and revelling in the special stripped-down approach. Some of the material, the other two F's were clearly happy with but Fish joked about some of the older material and how nervous it made them... Indeed, some of the tracks were so old that it is clear that Channel 4's Time Team must have been drafted in to help recover them. I assume this to be the case as there were so many bald heads and big beards in the crowd that it was clearly a Time Team night-out! Anyway, it won't spoil the tour too much to share a site-specific gag from Fish - he was actually married in this church in the late 1980's and recounted standing at the front with his two Best Men, a few feet from where he was performing, waiting for his German bride to arrive, slightly worse for wear from brandy in the hip flask, terrified by the thought of all the marzipan from all the weddings that had taken place in the church, imagining that it would fill the whole church. More on marzipan later...

So, there were old Marillion tracks (as Fish mentioned them on his Facebook page, I'm not giving spoilers by saying that they played "Jigsaw" and "Punch and Judy" - fantastic versions) and a catalogue of solo career tracks, right up to date with stuff from 13th Star. Fish, as ever, wore his heart a-sleeve, 'fessing up to having been given the curse of being rubbish at relationships, balanced Yin for Yang, by the gift of being able to write about them. He also is still clearly interested in the story and fate of young working class Scottish lads who end up in the British Army, sent off to hellhole conflicts around the world and then just dumped back here to pick up the pieces afterwards - and there are numbers in this set that reflect that concern. I still like his open, confessional style on stage, and that, with his taking a seat down at our level on the front of the stage (because he was knackered and the other two had seats) created a great intimate feel for the audience, certainly those at the front:

|

| Sorry abut the poor quality pic - my phone camera isn't the best! Fish, Professor of Angst-Filled Bravado at the University of The Broken Heart takes a seat and has a chat! |

And to recount the sum total of Fish's swearing for the night - it was ... none - he was a good boy and didn't swear (at all!) in church! And so, on the subject of marzipan...

Fish recalled, during Friday night's gig, his wedding day thought that all the marzipan from all the weddings that had taken place in the church might fill the whole church. I thought that deserved more attention so... I've done some calculations. Stick with me ("Listen to me. Just hear me out. If I could have your attention?"). We need to know: volume of marzipan per wedding cake and hence per wedding; number of weddings per year; how long weddings have been held (i.e. number of years = age of church), and the volume of the church. I've had to make some assumptions... I assumed that marzipan is sold in packs that are 15x10x10 cm (0.15x0.10x0.10 metres) in size, and that 10 packs are used for the average wedding cake. That means that the volume of marzipan per wedding cake and hence per wedding is 10x(0.15x0.10x0.10) = 0.015 cubic metres of marzipan per wedding. I've assumed that there are 400 weddings a year, which seems high but is only 8 per week in East Lothian's biggest church. Here's the fun bit - Google Brothers Inc. reveals that construction of St Mary's Church began in 1380 so, assuming people started being wed there from that date (in anticipation that it would be finished one day in the future, as indeed it was), that means there have been weddings for 630 years!

So, we have a total volume of marzipan over the lifetime of the church, equal to:

Volume of Marzipan per wedding x Number of Weddings per year x Number of years =

(0.015x400x630) or a total volume of 2835 cubic metres of marzipan. So, to see if that would fill the church (it does sound like a lot of marzipan, doesn't it?), we need to know the volume of the church. Where to find that? Luckily, being a popular tourist location, there is lots of information on the church to be found at the excellent Google Brothers Inc (other infromation providers are available). The church is 63 metres long and 35 metres wide, but alas, no information is provided on the height (volume of the church, being roughly right-angled at the corners - it is 630 years old after all - is length x width x height). But I was there on Friday, and I would estimate that the average height might be 8 metres. the total volume would therefore be 63 x 35 x 8 = 17640 cubic metres.

Oh... but that's a lot more than the estimated volume of marzipan. In fact, we can calculate the depth of marzipan by dividing the volume of marzipan by the floor area of the church (because depth = (volume/(length x width)). So, that would be 2835/(63 x 35) = almost 1.29 metres. So, a paltry depth of marzipan that would barely reach Fish's waist (he is quite tall). What a shame! But ... wait one minute - all may not be lost!

When did you ever go to a wedding and see the marzipan in blocks. At the wedding, it is ALWAYS already on the cake! So, I think we can have another go at this, assuming that all wedding cakes have three tiers (they do, don't they?). I reckon the following dimensions are more than reasonable for the three tiers of wedding cakes: upper - 20x20x10 cm; middle - 30x30x20 cm; lower - 40x40x30 cm. Yes, that would be a great wedding cake. Now, instead of the volume of marzipan (we can still assume 10 packs are used, but it doesn't matter now), we have a volume of (0.2x0.2x0.2)+(0.3x0.3x0.2)+(0.4x0.4x0.3) = 0.07 cubic metres. The wedding cakes are effectively marzipan boxes filled with cake and we need to know the total volume of marzipan boxes. That means our new calculation would be:

Volume of Marzipanned cake per wedding x Number of Weddings per year x Number of years = (0.07x400x630) = 17640 cubic metres which is equal to the volume of the church - fantastic! So, Fish, the church would be marzipan filled SO LONG AS IT WAS ON THE WEDDING CAKES (and assuming my very reasonable assumptions are correct...)

Interestingly (if you are a bit sad), this figure was calculated to 2010 so, when Fish was standing at the altar in the late 1980's awaiting his bride, there was in fact a small gap somewhere at the top of the metaphorical marzipan-filled church awaiting the next 20 years (approximately) worth of marzipanned cakes.

PS If you thought that a headful of chocolate frogs was bad (see above), I found this while looking into marzipan: marzipan frogs. Help!

Monday, 25 October 2010

Signs I Like #13

Recently, I had to go to a meeting at Longannet Power Station, where I receommend that anyone suffering from an over-inflated sense of their own importance should go for a visit - I've never felt so much like an ant, walking around beside the biggest building I have ever seen or been near. Anyway, while I was there, I spotted this cool sign on the ground, as I was leaving the visitors' car park. Serious safety culture at this place but it amused the pedant in me to ponder whether either the car park was unsafe, or if it was the case that unsafe behaviour was acceptable there... I also like the way that the shadow of the triangular warning sign is like an arrow, pointing to the exact location where safety starts...

Saturday, 23 October 2010

Signs of the times: Summer #21

More comparisons between the British countryside of today and that from 1959-1961 in the paintings of Charles Tunnicliffe in the Ladybird "What to look for..." series of books.

“In Flanders fields the poppies grow

Between the crosses, row on row,

That mark our place: and in the sky

The larks, still bravely singing, fly

Scarce heard amid the guns below.

We are the Dead. Short days ago

We lived, felt dawn, saw sunset glow,

Loved and were loved, and now we lie

In Flanders fields.”

Colonel John McRae, “In Flanders Fields”, 1915

(Copyright: Ladybird Books)

Summer Picture 21

Well, here we are, confronted by an image of a Summer that is long gone, although… although… just over a week ago, on a train journey from Edinburgh to Stirling, I saw a farmer collecting a very late season harvest of silage – hey, it’s still Summer after all! (No it isn’t – there was snow on the mountains around Stirling this morning…)

This is a really lovely image, bursting with life and colour. A big flock of house sparrows is raiding the seeds from ripe wheat. Around the margins of the wheat field, the yellow ragwort and creeping thistle are growing interspersed with red poppies. On the ragwort are feeding the black and yellow striped caterpillars of the cinnabar moth, and common blue butterflies flutter from flower to flower.

As we’ve looked at the decline (and possible subsequent rise) of the house sparrow in an earlier Spring post, here, this post will focus more on the flowers of agricultural land and field margins, and their associated insects.

The red flowering Common poppy (Latin name: Papaver rhoeas) is, according to Richard Mabey’s Flora Britannica, one of the world’s most successful “weeds” and has “followed and exploited the spread of farming across the globe so comprehensively that no one is sure of its native home.” An annual plant, it is found in arable fields and on other disturbed habitats. And it is that habitat preference that meant that, as the first early city-based societies formed 4-5000 years ago in the Middle East around a growing culture driven by arable agriculture, the common poppy was there and ready to benefit from this massive and relatively rapid increase in the area of its habitat.

And just thinking about the importance of natural processes influencing culture, it is that habitat preference of growing in disturbed soils that led to the iconic image of the red poppy as a commemorative symbol for the dead of two World wars and other conflicts. The hellhole trench warfare battlefields of World War One in northern France and Belgium, with their shell-torn and trench-riven land surface, created huge areas of disturbed soils that were colonized by millions and millions of red poppies, leading to the adoption of the red poppy as the ultimate symbol of commemoration. Richard Mabey suggests that the first common poppies probably arrived in Britain mixed in with the seed corn of the first Neolithic settlers. The New Atlas of the British and Irish flora suggests that “although there have been losses around the edges of its range, the overall distribution is remarkably stable”. This is strange, as I think the common perception amongst conservationists is probably that a major effect of the increase in the use of herbicides to control agricultural “weeds” from the 1960’s onwards was a decline in the fortunes of plant species like the common poppy. From the early 1970’s, I do have vivid memories of seeing cereal fields in East Lothian in early summer with a red dusting of poppies scattered through them, something that 10-15 years later was not a common sight. But the range could be the same with many fewer poppies as a whole, if the species remained in field margins and on other, non-agricultural, disturbed ground and also, the policy of set-aside no doubt helped the return of poppies to recolonise agricultural areas from the late 1980s onwards. A very welcome return, I say!

The Creeping thistle (Cirsium arvense) in the picture is usually found (according to the New Atlas) in “over-grazed pastures, hay meadows and rough grassy places, roadsides, arable fields and other cultivated land, and in urban habitats and waste ground.” In terms of its status, although listed as a noxious weed in Britain under the 1959 Weeds Act, there has been no change in distribution since the 1962 Atlas and probably little over many decades before that.

The Common Ragwort (Senecio jacobaea) is species that raises high emotions in this country! As Richard Mabey says in his For a Britannica: “Ragwort is regarded as the great enemy by those who keep horses, and summer weekends spent laboriously hand-pulling and removing the plants are a regular chore to check the plant’s spread. Neither horses nor other grazing animals will normally eat the growing plant, unless it is so dense that it is difficult to graze without ingesting some, but they will when it has died and dried. Green or dry, it causes insidious and irreversible cirrhosis of the liver.” Nice! According to the New Atlas: “It is a notifiable weed, subject to statutory control, but this has clearly had little, if any, effect on its distribution or abundance.” In fact: “The distribution of S. jacobaea is unchanged from the map in the 1962 Atlas.” Interestingly, for such a supposedly noxious plant (here in Stirling, apparently, it is or was called stinking alisander), Tess Darwin, in her “Scots Herbal”, reports that, not only was it uprooted and used in a playground chasing game in the Hebrides, but it has traditionally been used for a range of medical purposes. The astringent juice was used “to treat burns, eye inflammation, sores and cancerous ulcers, as a gargle for an ulcerated throat and mouth and for bee stings.” Poultices were also made from the green leaves and applied for rheumatism, sciatica and gout, while “a decoction of the root was taken for internal bruising and wounds”. Drawing your attention back to “insidious and irreversible cirrhosis of the liver”, I say rather them than me... Common ragwort was also used to produce bronze, yellow and green dyes.

I don’t think it wouldn’t be right to talk about the Common Ragwort without also discussing the Cinnabar moth (Tyria jacobaeae), something that was obviously also on the mind of Charles Tunnicliffe, who included the orange and black striped caterpillars of the moth in the painting, doing what they normally do, feeding on the leaves of the common ragwort. Even the second part of Latin name of the moth (“jacobaeae”) tells us that the moth is “of” the ragwort! As reported by Butterfly Conservation’s report, “State of Britain’s Larger Moths”, the Cinnabar is one of the most familiar larger moths “on account of its attractive black and red wings and because of its distinctive orange and black banded caterpillars found on ragwort.” This moth species is widespread and common in southern Britain, but its distribution in Scotland is more local and coastal. Butterfly Conservation does report, however, that its populations have suffered a long-term decrease of 83% over 35 years, marking the species as “Vulnerable” according to the conservation criteria of the World Conservation Union (IUCN). It isn’t clear why this is happening, since the overall distribution of ragwort, its host plant, remains relatively unchanged, as reported above.

Both the adult moth and the caterpillars taste bitter to birds that eat them, and the coloration (the bright red on adults, and the black and orange stripes – a common warning coloration in nature!) may be intended to deter predation. This species is the first one for which I understood that there could be plant-insect interactions that meant that some insects were dependent on specific species of plant. When, as a young boy, I used to accompany my Dad when he was out patrolling as a countryside ranger, we would see ragwort plants growing in the dune grasslands (for example, at Yellowcraig, near North Berwick), covered in cinnabar caterpillars (which we never saw anywhere else, on any other plant). By the end of the Summer, a large proportion of the ragwort plants were (and still are) stripped down by the caterpillars to bare, leafless, flowerless stalks.

On those childhood trips where I began to learn through observation about the natural history of dune grasslands we would usually see numerous Common blue butterflies (Polyommatus icarus), perhaps not surprisingly, as it is one of Britain’s commonest species. Its caterpillars feed on bird’s foot trefoil, clover and related species. Butterfly Conservation has reported, in its State of Butterflies in Britain and Ireland, that, despite some evidence of decline at a local scale, nearly all the places where it was recorded in the 1970’s, still had records between 1995 and 2004. Butterfly Conservation does highlight, however, that the Common Blue continues to face threats from habitat loss and deterioration and that its status should be closely monitored as an indicator of the state of biodiversity in the wider countryside.

I hope you’ve enjoyed this particular post – this current picture of a field of grain near harvest is, in my view, a joy to look at, and it represents the last clearly summery picture in the Ladybird Summer book. The three final images from the Summer book look increasingly Autumnal, as you will see over the next few days.

Monday, 18 October 2010

Hubba hubba Hubble!

(This is the kind of post I would expect to see over on e-clecticism, so hopefully jono will forgive me for this parking of scooters on his lawn!)

So, the magnificent Hubble telescope is 20 years old. For me, the Hubble and the images it produces of deep space (and, hence, the distant past) are one of the Wonders of the Modern World. A truly extraordinary technological and scientific feat. The Grauniad newspaper (ok, The Guardian) has an excellent and interesting narrated slideshow (from yesterday) about Hubble and its discoveries here. Apologies that you have to follow a link, but there didn't seem to be an option to embed the article (and I'm ham-fisted about this stuff, if it isn't obvious). But go on, have a look, and gawp, open-mouthed, at the deep space pictures produced by this massive peeping tube in space. It is staggeringly difficult to comprehend the spatial scale of some of these structures in deep space, when the narrator says something about the little blobs on one image being of the order of a light year across.

And if you really like these views of deep space, you can see much, much more here, on the NASA Hubble site.

So, the magnificent Hubble telescope is 20 years old. For me, the Hubble and the images it produces of deep space (and, hence, the distant past) are one of the Wonders of the Modern World. A truly extraordinary technological and scientific feat. The Grauniad newspaper (ok, The Guardian) has an excellent and interesting narrated slideshow (from yesterday) about Hubble and its discoveries here. Apologies that you have to follow a link, but there didn't seem to be an option to embed the article (and I'm ham-fisted about this stuff, if it isn't obvious). But go on, have a look, and gawp, open-mouthed, at the deep space pictures produced by this massive peeping tube in space. It is staggeringly difficult to comprehend the spatial scale of some of these structures in deep space, when the narrator says something about the little blobs on one image being of the order of a light year across.

|

| Screen dump from the Guardian website (Copyright: The Guardian) |

And if you really like these views of deep space, you can see much, much more here, on the NASA Hubble site.

| Credits: X-ray: NASA/CXC/SAO/J.DePasquale; IR: NASA/JPL-Caltech; Optical: NASA/STScI |

Wednesday, 13 October 2010

Monday, 11 October 2010

Signs of the times: Summer #20

More comparisons between the British countryside of today and that from 1959-1961 in the paintings of Charles Tunnicliffe in the Ladybird "What to look for..." series of books.

“Relatives are the worst friends, said the fox as the dogs took off after it.”

Anonymous Danish proverb

(Copyright: Ladybird Books)

Summer Picture 20

A moorland scene that could be from Scotland, Yorkshire or, at the time the book was published, Cumberland. Let us, from my Scottish bias, assume it is a Scottish moorland. A small flock of red grouse look on as a red fox, a potential predator, is running off to the right of the picture. A dipper sits on a rock in the stream, above some small brown trout sitting in the current. Both the bell heather and the ling heather are in flower, with small dark blue fruit growing on the bilberry plants in the bottom right. A high-brown fritillary butterfly flutters nearby, while an emperor moth caterpillar is feeding on the ling heather. We’ve looked at the brown trout in an earlier post, here, so I won’t discuss it again now.

The red grouse (Latin name: Lagopus lagopus) is a native game bird, the distinctive dark-winged scotica race being endemic to Britain and Ireland and with the great majority of its population within the UK. Those unfamiliar with it may well recognize it as the cartoon caricature bird that stars in the amusing adverts for “The Famous Grouse” blended Scottish whisky. The British Trust for Ornithology describes how the red grouse is economically very important to some rural communities as a game bird and has benefited from intensive management of many moorlands, designed specifically to increase the numbers of grouse available to be shot. There are no accurate survey figures for red grouse populations going back to 1960, but BTO shows that there have been fluctuations in red grouse populations, but no overall trend, since 1994:

(From: British Trust for Ornithology)

Shooting bags, from figures collated by the Game and Wildlife Conservation Trust, (i.e. the number reported as having been shot) have revealed long-term declines, apparently driven by the loss of heather moorland, increased predation from corvids (crows and ravens) and foxes, and an increasing incidence of viral disease. In conservation terms, this decline resulted in the moving of this species from the “green” (safe) list to the “amber” list. The BTO’s account does an excellent job of summarizing the complex and complicated interaction of natural processes and human interference affecting grouse: “Longer-term trends in Red Grouse abundance are overlain by cycles, with periods that vary regionally, linked to the dynamics of infection by a nematode parasite ... Raptor predation is believed not to affect breeding populations significantly, although it can reduce numbers in the post-breeding period ... Hen Harriers in particular can reduce grouse shooting bags, limit grouse populations and cause economic losses to moor owners, and have been subject to much illegal persecution ... Finding a solution to the harrier–grouse conflict would bring considerable benefits to the management of the UK's heather moorlands and have broad implications for the conservation of predators.”

And on the subject of predators of red grouse… Most people probably don’t think about it in these terms, but the red fox (Vulpes vulpes) is Britain’s only surviving native wild dog species, following the elimination of the last wolf in the 18th Century and, possibly, the prehistoric retreat northwards of arctic foxes with the retreat of the ice fields of the last Ice Age. The Joint Nature Conservation Committee’s review of British mammals provides an estimate of the fox population of Britain as around 240,000, of which Scotland has around 23,000. The JNCC reports that the fox population of Britain is probably still growing, including the phenomenon of urban foxes. As you’ll know if you watch the BBC Springwatch programmes which always seem to feature films of them, foxes are increasingly found in urban habitats, with around 3000 urban foxes estimated in Scotland.

A few winters ago, we had a resident fox living in or around our garden, much to the frustration and occasional excitement of Ella the Wonder Dog. It made its way around the area on the top of the six foot high walls between the gardens and, where we had a large growth of ivy growing over the top of the wall, it used to sleep there, under the ivy cover, curled up with its large tail (or brush) wrapped around it. Occasionally we would see, reflected in our torch light, a single shining eye open up to check that we weren’t approaching too closely, but otherwise it ignored us completely... whereas every time the fox was “staying”, Ella ran back and forward in a frustrated growling frenzy, at the bottom of the wall!

No doubt there is still active game-keepering activity on the grouse moors of Britain, perhaps accounting for the nervous disposition of the fox in this picture! There’s lots more to say about the fox’s place in British ecology and culture, but the fox, and fox-hunting feature in the Autumn book, we’ll revisit this later in the year (but not too much later).

The dipper (Cinclus cinclus) is the little dark brown, chestnut brown and white bird standing on the rock in the stream. It is unique among the passerine (or perching) birds of Britain as the only one that feeds from the bottom of streams and rivers, plunging in, walking upstream into the current and feeding on riverine insect larvae and other stream invertebrates ( it isn’t the ONLY species that dives into freshwaters to feed though – consider the kingfisher!). The BTO provides a picture of the long-term fate of Britain’s dipper population. Dipper populations have fluctuated over the last thirty years, but with an overall downward trend:

(From: British Trust for Ornithology)

Dippers are very sensitive to the acidification of rivers (from acid rain), which leads to the loss of their invertebrate prey. Not surprisingly, the acid rain problems of the 1970’s badly affected dippers in the uplands where acidification was worst. Since 1975, there has been a 30% decline in the dipper population, although there is probably now an ongoing recovery from acid rain problems in many of Britain’s worst affected freshwaters in recent years (I can find you evidence if you need it!). I speculated previously here on the possible recovery of dippers. In our recent Corsican adventure, we were surprised (presumably unreasonably so) and delighted (not unreasonably) to see dippers regularly in the rocky river running through the mountain city of Corte.

The overwhelmingly dominant plant in this picture is heather. The painting purports to show two species, bell heather (Erica cinerea) and ling heather (Calluna vulgaris). Erica cinerea, named bell heather on account of its small purple bell-like flowers has ,according to the New Atlas of the British and Irish Flora, declined in southern England from loss of heathland habitat, and has disappeared from many former 'chalk heath' sites through encroachment of rank grass and scrub following reduction in sheep and rabbit grazing. The ling heather (Calluna vulgaris) is also reported in the New Atlas to have declined as suitable habitat has declined greatly, particularly in much of England, “since 1950 through loss of heathland to forestry, agriculture, mineral workings and scrub. It cannot tolerate continued heavy grazing, and has declined in some upland areas for this reason.”

According to Tess Darwin, in “The Scots Herbal”: “Of all Scottish wild plants, the prize usefulness must surely go to heather. In a typical dwelling in many parts of Scotland until this century, heather might have been found in the walls, thatch, beds, fire, floor mats, ale, tea, baskets, medicine chest and dye pot, being used to sweep the house and chimney, to feed and bed down sheep and cattle and to weave into fences around the farm”. Phew! Also, very sagely, she points out that, while many people consider heather to be just as much of an emblem of Scotland as the thistle, although heather moorland is “an artificial and degraded landscape created by deforestation and maintained by over-grazing of sheep and deer and burning for grouse management.” Phew!

The bilberry (Vaccinium myrtillus) in the extreme bottom right of the picture, known in Scotland as the blaeberry and in Shropshire and the Welsh Marches as the wimberry, is also a member of the Heather family. Blaeberries are an important wild food resource, the collection of which in Britain took a bit of a dent following the contamination of many British upland areas by the Chernobyl explosion’s fallout. Tess Darwin points out that, as well as a food source, in Scotland, they have also been used as a treatment for kidney stones and as a dark purple blue dye for cloth. The New Atlas reports declines in the blueberry from the edge of its range: “in England since 1950, reflecting the loss of lowland heathland. It has also declined in C[entral] Ireland, probably for the same reasons. Elsewhere it remains common in suitable habitats.” My wife is obsessed with harvesting blaeberries when we find ourselves among fruiting bushes when out hill-walking. In such circumstances, there is little point in me expecting to go any further for some considerable time.

Just to finish off this rather long post, there are two insects featured, the high brown fritillary butterfly and the caterpillar of the emperor moth. The high brown fritillary (Argynnis adippe) has, since the 1970’s, suffered the greatest distribution decrease of any surviving butterfly species in Britain and is now one of our most threatened species. The NGO for butterflies, Butterfly Conservation reports a 79% decline in distribution, and a decline of 85% in monitored populations between 1995 and 2004. This may all be down to changes in the way that moorland and upland forest edge habitats have been managed, as positive habitat management in England has brought about local increases in populations. The emperor moth (Saturnia pavonia) is common across Europe and its caterpillar feeds on bramble, heather and other shrubs. I couldn’t find any detail about how it is doing in Britain, although I did read that emperor moth males can detect the pheromones of the females up to five miles away.

Saturday, 9 October 2010

Ukulele tribute to John Lennon

Continuing the over-riding musical theme of today, the day that would have been John Lennon's 70th birthday, here is a wonderful, heartfelt tribute to him from a bunch of ukulele players - little snippets of covers of Lennon and Beatles songs. I love this and I hope you enjoy it too. Some are very sophisticated, and some are just simple and fun.

Happy Birthday, Mr Lennon...

I'm sure it would have been a great party for John Lennon's 70th birthday today... here's what we've been missing all these years:

Just imagine...

Just imagine...

Thursday, 7 October 2010

Pedants walk among us...

The Purist

I give you now Professor Twist,

A conscientious scientist,

Trustees exclaimed, "He never bungles!"

And sent him off to distant jungles.

Camped on a tropic riverside,

One day he missed his loving bride.

She had, the guide informed him later,

Been eaten by an alligator.

Professor Twist could not but smile.

You mean," he said, "a crocodile."

Ogden Nash

I give you now Professor Twist,

A conscientious scientist,

Trustees exclaimed, "He never bungles!"

And sent him off to distant jungles.

Camped on a tropic riverside,

One day he missed his loving bride.

She had, the guide informed him later,

Been eaten by an alligator.

Professor Twist could not but smile.

You mean," he said, "a crocodile."

Ogden Nash

Tuesday, 5 October 2010

Signs of the times: Summer #19

More comparisons between the British countryside of today and that from 1959-1961 in the paintings of Charles Tunnicliffe in the Ladybird "What to look for..." series of books.

"Always carry a flagon of whiskey in case of snakebite and furthermore always carry a small snake."

W. C. Fields

(Copyright: Ladybird Books)

Summer Picture 19

As you’ll have seen from my recent posts about our Corsican trip, I’ve had a reptile-rich time in the past few weeks. So it is quite a pleasure to see a snake taking centre spot in the next Summer picture. This adder is sitting basking in the sun in a coastal dune system, rich with beautiful flowering plants. A grayling butterfly has settled on the flowers of thyme in the foreground.

In the very top left of the picture, closer to the sea and growing on more unstable sand is marram grass (Latin name: Ammophila arenaria), one of the plant species that helps to stabilize mobile sand dunes, which ultimately assists the other plant species in the picture to colonise and grow in this habitat. This stabilizing attribute has also led to this species being deliberately planted to help restore blow-outs in sand dune systems, or to help with the building of dunes for coastal protection purposes. Marram is beautifully adapted for life in this harsh, dry environment. It has a thick and waxy cuticle on its leaf to prevent water loss, and the leaf is rolled into a tight tube to reduce the exposure of leaf surface to dehydrating winds. The New Atlas of the British and Irish Flora indicates that, since 1962, the overall distribution of this species is largely unchanged, the deliberate planting having had little effect on this.

The little pink-purple flowers of the wild thyme (Thymus polytrichus) are scattered throughout the picture. According to the New Atlas, it is a “perennial herb of free-draining, calcareous or base-rich substrates, including chalk, limestone, sands and gravels. It occurs in short grassland on heaths, downland, sea-cliffs and sand dunes, and around rock outcrops and hummocks in calcareous mires. It is also frequent in upland grassland and on montane cliffs, rocks and ledges”. Although the Atlas says that there is some evidence for losses in the southern part of its range, wild thyme remains very common in suitable habitats. The concentration of the aromatic volatile oil thymol in this wild species is high enough to allow the use of this species in cooking (we’ve used it while camping). According to Richard Mabey in his Flora Britannica, it was sometimes used in Scotland as a substitute for lavender to sent clothes, handkerchiefs and household linen.

In the top-right of the picture are a couple of carline thistles (Carlina vulgaris), a distinctive plant of short, dry grasslands such as this one. The New Atlas says that it has suffered a widespread decline, with most losses having occurred since 1950. “Losses are partly due to habitat destruction and a lack of grazing”. It is very restricted in its distribution in Scotland, to a few coastal sites, although much more widely spread inland in England.

In the bottom right and to the left of the adder are the yellow flowers of the lady’s bedstraw (Galium verum), which can be found in suitable habitats from June to September (phew – I’m not completely off-schedule yet!). Flora Britannica collates interesting uses for this plant – it dries to give the smell of new-mown hay and in full flower, it smells strongly of honey. Its name probably comes from the custom of putting it in straw mattresses, especially for the beds of women going into labour. It also has coagulant properties and provided a vegetable substitute for rennet in cheese making. In fact, this was obviously a widespread use – Tess Darwin, in her book “The Scots Herbal. The Plant Lore of Scotland” reports a Scottish name “keeslip” (= cheeseslip) and the Gaelic name “lus an leasaich” (= rennet plant). In a link to this post’s coverage of sand dune plants, Tess Darwin also includes a report from an 18th Century traveller to the Isle of Barra in the Western Isles, where the collection of the extensive growths of this species, for use in dyeing of tweed, was leading to the erosion of the machair grasslands, indicating both another important historical use and the binding effect of its root system. In fact, collection of lady’s bedstraw was banned there to prevent erosion. The New Atlas reports that, although there have been some localised declines in this species since 1962, it remains common across much of its range and is a frequent constituent of wild-flower seed mixtures.

The adder (Vipera berus) is Britain’s only venomous snake which is rarely dangerous but can deliver a painful bite. It is widespread in heathlands across Britain. In Scotland, Scottish Natural Heritage says of the adder: “They are widespread but absent from much of the Central Lowlands, the Outer Hebrides and Northern Isles. Adders are found on heathland, moors, the borders of woods and fields, overgrown quarries and railway embankments. They tend to bask around sunny edges of dense ground vegetation, which provides a good source of warmth and deep cover, into which they can quickly escape when disturbed. They are absent from areas of intensive arable farming.” The BBC website has some useful background information on the adder here.

For an assessment of the status of the adder in Britain (in conservation terms), I went to the website of the Joint Nature Conservation Committee, here. According to this source, this snake species is still persecuted as well as suffering from habitat fragmentation, afforestation, public pressure, inappropriate habitat management and (inevitably) development and general tidying of the countryside. Severe declines in several English counties have already been reported ( Warks, Worcs, Wyre Forest, London, Herts). Adder population decreases have been recorded in all English regions studied, but were was most marked in the Midlands. For example, the only known adder site in Nottingham was damaged by forestry works in 2003 and the current status of that population is unknown, and monitoring in the Wyre Forest has detected decreases in the number of populations and of individuals within them (from 150-200 individuals in the early 1990s to 20-30 individuals in 2004-5- despite this being a protected site).

In Scotland, a good general publication on Scotland’s reptiles and amphibians can been found here. For Scotland, we are fortunate also to have a report on the status of the adder in Scotland, commissioned by Scottish Natural Heritage, which you can see here. Unfortunately, it is quite dated, having been published in 1994 (while I worked for SNH, although I had nothing to do with this report). This concluded that, at that time, the status of the adder compared favourably with that of the rest of the UK (except SW England, where the adder is common). While the adder was perceived to have declined in more intensively farmed areas, it was apparent that it had not suffered the more widespread declines reported in England during the 1980s. The report concluded that Scotland represented an important upland area in the distribution of the adder as it is not only extensive but relatively undisturbed and remote. Work is underway nationally and locally to take conservation action for adders in Scotland. For example, there is an adder action plan as part of the City of Edinburgh Biodiversity Action Plan, which you can view here, and another as part of the Dumfries and Galloway Biodiversity Action Plan, which you can read here.

The grayling butterfly (Hipparchia semele) which is sitting on the purple thyme flowers quite inconspicuously in the picture’s foreground is a member of a species that, since the 1970s, has been in serious decline. The main conservation organisation for butterflies and moths, Butterfly Conservation, in its report on the State of Butterflies in Britain and Ireland, showed that, between 1976 and 2004, the British population of this butterfly species declined by 51%, and between the two periods 1970-1982 and 1995-2004, the distribution (the number of places the species is found) has declined by 45%. Butterfly Conservation says that such a decline in this species would have been unimaginable to entomologists of a generation ago.

Possibly, the decline in coppicing of woodlands, and the consequent decline in the creation of new clearings with their early successional stages of recovering coppiced woodland, has resulted in habitat loss for the grayling butterfly. This loss might have been offset a little by the early growth of scrub habitat on brownfield (that is, previously developed and now derelict) land, some new populations of grayling butterflies have been found, for example, on such sites alongside the River Tees in Middlesbrough, where conservation action has been taken to protect the butterflies at these sites.

Friday, 1 October 2010

Signs of the times: Summer #18

More comparisons between the British countryside of today and that from 1959-1961 in the paintings of Charles Tunnicliffe in the Ladybird "What to look for..." series of books.

“The swallow of summer, the barbed harpoon,

She flings from the furnace, a rainbow of purples,

Dips her glow in the pond and is perfect.”

Ted Hughes, from: "Work and Play"

(Copyright: Ladybird Books)

Summer Picture 18

Och, a wee holiday away for two weeks and summer seems to have fled by our return at the weekend. I’d better press on! Fortunately, the main subjects of Summer picture 18 are still here in central Scotland, with the swallows and swifts still winging their way around. In the foreground, the seed heads of bulrushes (or reed-mace) from last year have burst to release their downy seeds, while this year’s new seed heads are still forming. A flock of Canada geese is swimming in the background.

Swallows and swifts have already featured in this blog series, where I looked at how they have fared here for the swallow and here, the swift. Although swifts may begin leaving for their African winter haunts much earlier in the summer, the swallow is one of the latest species to depart, mostly by late September. The gathering of noisy flocks on telephone wires is a sure sign of the impending end of the summer season and then, one day, they have mostly all gone, other than the odd straggler, perhaps the product of a later second brood.

Canada geese are not a native species to Britain. In fact, although they have been here for several hundred years and were introduced deliberately (Giant Hogweed, anyone?), they are now regarded as an invasive non-native species. The introduction must have been for ornamental reasons as Canada Geese are reputedly amongst the most inedible of birds (Move along! Move along – there’s no wild food story ‘ere”).

You can find out more about the Canada Goose problem and what is being done about it here, on an advisory site run by the Non-Native Species Secretariat for Great Britain, where you can pick Canada Goose from the list. This site characterises the problem of Canada Geese in Britain as follows:

Ecosystem Impact: Introduced geese are heavy grazers of aquatic and waterside vegetation, and their droppings can increase nutrient levels in water bodies and soils. Trampling and the addition of nutrients can change the composition of plant communities, especially where grazing is intense.

Health and Social Impact: There is considerable concern that the presence of so many large birds in close association with people, for example in urban parks, may be a health hazard. Canada geese are suspected of transmitting salmonella to cattle. The presence of slippery droppings can be a nuisance, especially on paths, playing fields or golf courses, as can possible aggression from nesting adults. Bird strikes involving Canada geese have caused human deaths and injury as well as damage to the environment and loss of or damage to aircraft.

Economic Impact:Canada geese may graze on farmland at any season, occur very widely, and may feed in areas that would be shunned by wild geese. Their grazing and trampling may cause major damage to grassland and crops. Birds climbing out from the water to graze make shallow, well-trodden paths that can damage flood defences and accelerate bankside erosion.

The British Trust for Ornithology reports, of this species: “Canada Geese were first introduced to English parkland around 1665 but have expanded hugely in range and numbers following translocations in the 1950s and 1960s. They increased rapidly, at a rate estimated at 9.3% per annum in Britain between the 1988–91 Atlas period and 2000, with no sign of any slowing in the rate of increase”. That rate of growth looks something like this:

(From: British Trust for Ornithology)

The BTO concludes that: “The economic, social and environmental impacts of rapidly expanding, non-native Canada Goose populations are of growing conservation concern across Europe” [see above!].

On a happier note, the bulrush or reedmace (Typha latifolia) in the front of the picture is a native plant, which the New Atlas of the British and Irish Flora (2002) says is: “an emergent in shallow water or on exposed mud at the edge of lakes, ponds, canals and ditches and (less frequently) by streams and rivers. It favours nutrient-rich sites. It spreads by wind-dispersed fruits, often colonising newly excavated ponds and ditches and subsequently spreading by vegetative growth”. In terms of its success, the New Atlas says of this species that there is some evidence that it increased in frequency in the 20th century in many areas, for reasons that are not entirely clear. It is now much more frequently recorded in Wales, northern England and Scotland than it was in the 1962 Atlas. Richard Mabey, in his Flora Britannica, reports that surprisingly little use has been made of Typha in Britain, confirmed by the only entry for the species in Tess Darwin’s “The Scots Herbal”, where it is reported from an early 19th century account from Orkney which reports that it was added to some poor hay mixture of local plants, of which it was said: “None but the half-starved beasts of Orkney would eat such fodder”!

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)